- Gateway to Arunachal

- Dec 4, 2025

- 3 min read

Nestled in the remote eastern Himalayas of Arunachal Pradesh, India, Dri Valley (often stylized as Dri~mo in local contexts, reflecting the Idu Mishmi pronunciation) is a breathtaking alpine haven that has earned the moniker "Shangri-La of Dibang Valley." This ethereal landscape evokes the mythical paradise from James Hilton's *Lost Horizon*—a harmonious blend of pristine nature, spiritual lore, and untouched wilderness where time seems to stand still. Just as Shangri-La represents an earthly utopia enclosed by towering peaks, Dri Valley offers a similar sense of seclusion, with its glacier-fed rivers, rhododendron forests, and snow-capped sentinels that guard ancient tribal traditions.

Why It's Called the Shangri-La

The nickname stems from the valley's otherworldly allure:

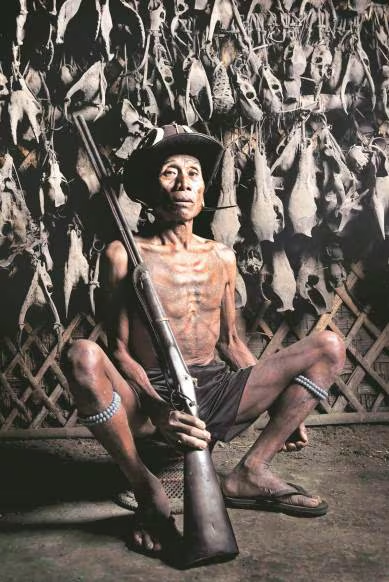

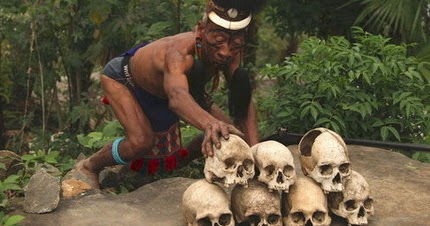

Mythical Isolation : Originating from the glaciers of the Kangri Karpo range - a near-mythical frontier rarely trodden by outsiders - Dri Valley merges Buddhist mysticism with the animist spirits of indigenous tribes like the Idu Mishmi. This cultural fusion creates a "balance of life" that travelers describe as paradisiacal, much like Hilton's fictional Tibetan enclave.

Natural Serenity : Enveloped by the Dibang Wildlife Sanctuary (spanning over 4,000 sq km), the valley features crystal-clear alpine lakes, virgin meadows, and passes like Yonggyap La at 13,000 feet. It's a biodiversity hotspot with rare species such as the Mishmi takin, red goral, and Sclater's monal pheasant, alongside endemic flora that blooms in vibrant carpets during spring.

Emerging Eco-Gem : Recent promotions highlight it as an "ideal spot" for eco-tourism, drawing adventurers seeking solitude amid Arunachal's frontier vibes.

In contrast to more commercialized "Shangri-Las" (like the renamed town in Yunnan, China), Dri Valley remains authentically wild and sparsely populated—Dibang Valley as a whole holds India's record for lowest population density at just 0.8 people per sq km.

Geography and the Dibang Connection

Dri Valley is a key tributary basin within Dibang Valley district, one of Arunachal Pradesh's most rugged frontiers:

The River's Journey : The Dri River bursts from Kangri Karpo's hidden glaciers, carving through the valley before merging with the Mathun to form the Dibang River. This mighty waterway then races southward, joining the Brahmaputra in Assam's plains—fueling the region's fertile lowlands.

Terrain Highlights : Expect steep gorges, terraced hillsides (once used for millet and potato cultivation), and elevations soaring to 15,000 feet in the Mishmi Hills. The valley's remoteness means limited roads—access often involves 13+ hour drives from Roing or Anini, with hairpin turns that test even seasoned drivers.

History and Exploration

Explored as early as 1913 by British officers F.M. Bailey and H.T. Morshead during boundary surveys, the valley has long captivated adventurers. Early treks followed punishing routes to passes like Yonggyap La, battling storms and isolation—echoing tales of "forbidden" Himalayan edges. Today, it's part of protected areas established in 1991, preserving its status as a "promised land" for trekkers and wildlife enthusiasts.

How to Visit (Practical Tips)

Getting There : Fly into Dibrugarh (Assam), then drive ~6–8 hours to Roing, followed by another 10–13 hours to Anini (Dibang HQ). From Anini, it's a rugged 4–6 hour off-road to Dri Valley trailheads. Permits (ILP) are mandatory for foreigners; locals need PAP.

Best Time : October–April (post-monsoon clarity; winters bring snow magic).

Activities : Multi-day treks to glacial meadows, birdwatching, river rafting on the Dri, or homestays with Mishmi families. Stay at basic guesthouses or camps—expect no luxury, but pure immersion.

Challenges : Unpredictable weather (e.g., sudden storms), limited connectivity, and Inner Line restrictions. Pack for altitude sickness and self-sufficiency.

Dri Valley isn't just a destination; it's a whisper from the Himalayas inviting you to lose yourself in its timeless embrace. If you're chasing that elusive paradise, this is where the mountains hide their secrets. Have you been, or planning a trip?