The Fading Echo of the Headhunt: Traditional Headhunting in Arunachal Pradesh & Nagaland

- Gateway to Arunachal

- Dec 4, 2025

- 4 min read

Headhunting: not savage bloodshed, but sacred harvest of soul-force, fertility, status, and manhood in the hills

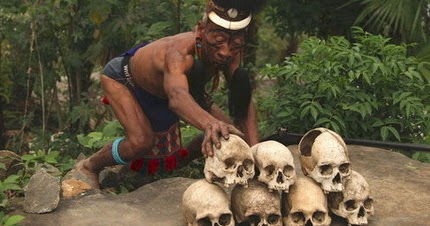

For most of the 20th century, the mere mention of “Nagaland” or the eastern tribes of "Arunachal Pradesh" conjured images of severed human heads hanging from bamboo poles in morungs (dormitories) or displayed on “head-trees” outside villages. Headhunting – the ritual taking of an enemy’s head – was once the defining cultural institution across dozens of Naga tribes and several Arunachali groups, including the Apatani, Nyishi, Adi Gallong, Wancho, Nocte, and Tangsa. It was never mere savagery; it was cosmology, social ladder, and rite of passage rolled into one.

Why Take Heads?

In the worldview of these hill tribes, the human soul cold-blooded murder was not the point. The head was believed to contain a person’s soul-force or fertility essence. Bringing an enemy head back to the village transferred that power to the rice fields, to the community, and especially to the warrior himself. A successful headhunter earned the right to wear distinctive shawls, tattoos, horn-shaped headgear (the famous gao), brass skull pendants, and the most coveted privilege of all – the right to marry.

Among the Konyak Nagas of Mon and Longwa, a man without at least one head was literally unmarriageable; he was considered incomplete, still a boy.

The Ao Naga proverb summed it up neatly: “Meat without salt is tasteless; a man without a head taken is worthless.”

The Golden Age of the Headhunt (1850–1950)

When British surveyors first penetrated the Naga Hills in the 1830s, they found villages in perpetual low-intensity warfare. Raids were planned around agricultural cycles – usually just after sowing or before harvest – because that was when the spiritual power of the head would benefit the crops most. Surprise dawn attacks were preferred. The war party crept through jungle, struck fast, decapitated the victim with a dao (machete-like blade), and fled before the enemy village could organise a counter-raid.

The heads were carried home in bamboo baskets, greeted with war cries and gongs. Over the next week came the great feasts of merit: rice beer flowed in rivers, mithuns (semi-domesticated gayal cattle) were slaughtered by the dozen, and the skull was ritually cleaned, smoked over the fire, and finally placed in the morung or on the village’s sacred banyan “head-tree”.

Tribe-specific Traditions

Konyak (Nagaland & Arunachal): The last great headhunting tribe. Facial tattoos were applied only after the first head; the more heads, the more intricate the tattoo. Until the 1960s, old men in Longwa and Chen villages still proudly displayed Japanese and Allied soldiers’ skulls from World War II.

Wancho (Tirap, Arunachal): Heads were kept inside the chief’s morung; gun barrels taken from enemies were bent into bracelets.

Nocte (Tirap): Practised “friendly headhunting” – they would sometimes buy heads from allied villages just to fulfil social obligations.

Apatani (Arunachal): One of the few tribes that largely gave up headhunting by the early 20th century after a peace treaty with the Nyishi, yet old bamboo skull-houses still stand in Hari village.

Tangkhul & Mao (Manipur-Nagaland border): The heads of women and children were considered especially potent for rice fertility.

The End of an Era

The death of headhunting came swiftly and from multiple directions:

British punitive expeditions (1870s–1940s) – any village caught with fresh heads was burned to the ground.

World War II – the arrival of thousands of American and Japanese troops in 1944 exposed the tribes to modern firepower and global scrutiny.

Mass conversion to Christianity – Baptist missionaries, starting with the Ao tribe in 1872, preached that headhunting was incompatible with the Gospel. By the 1950s, entire villages were baptised en masse.

Indian administration post-1947 – the new government made headhunting a capital offence. The last confirmed raid in India took place in 1969 when Konyak warriors from Longwa attacked a Tibetan refugee settlement across the border.

Even so, memory dies slowly. As late as 1991, two Yobin (Lisu) men in Vijaynagar, Arunachal, were beheaded in a boundary dispute. Old men still boast of their youth, and in remote Wancho and Yobin villages, human skulls – now yellowed with age – remain hidden under morung floors or inside hollowed logs.

Today: From Skull to Souvenir

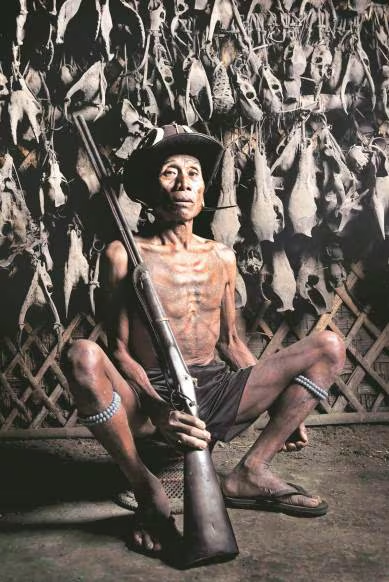

Modern Nagaland and eastern Arunachal have transformed the legacy. The famous Hornbill Festival (December 1–10 every year) features mock war dances, songs about past glory, and warriors wearing replica hornbill-feather headgear. Tourists buy miniature brass heads as keychains, unaware they are replicas of once-sacred trophies. In Mon district, ex-headhunters in their 80s and 90s pose for photographs – for a fee – beside the last authentic skull collections.

The headhunt is gone, but its echo still shapes identity. Ask a Konyak elder what made a man great, and even today he will tap his chest and say softly, “A man was measured by the heads he brought home.”

In the silence of the morungs now used as community halls, you can almost hear the ghosts of those heads whispering that, once upon a time, the hills themselves demanded blood for the rice to grow.

And perhaps, in the deepest jungle clearings where no missionary or district officer ever reached, a few old men still dream of the days when the dao was sharp and the path back to the village was lit by victory fires.

Comments